The Useful Pianist 5: Using Chords for Playing by Ear & Improvising RSS

The wonderful thing about pianos ...

The piano has many wonderful features, but one that sets it apart from other instruments is the possibility to play chords. Yes, I know guitars can do that too, which is probably why they are so popular as well, but only on the piano is it so easy to get a chordal texture of just about any size or shape you want.

Yet beginners in the UK often have to wait far too long before this exciting world is opened up for them. American method books seem to introduce chord playing sooner and this has spurred me to include chords from very early stages in all my students' learning.

This is not to say that it is simple. As a teacher, you have to make sure that it is all explained one step at a time, just like any other new piano concept. There are at least three different learning areas to cover:

- Technique - how to physically play a given chord

- Theory - names of chords, ideas like "root", and how they look on the page

- Choosing - which chord goes with which notes of the scale, and what sounds best, and why

Chord inversion

Chord inversion - a crucial concept - comes into all these categories, and yet you can also ignore it as a topic and simply dictate a set of chords to cover the basics. I call this approach "American-style chords" as it is based on what I have found in American beginner methods which introduce keyboard harmony skills early. The right hand plays the tune and the left provides the chords. "UK style chords", which I also teach according to the student's readiness, uses inversions in the right hand and a single bass line - mostly roots to start with - in the left. For more advanced students, this is also an essential part of aural training, enabling them to practise cadences by constructing them at home and understanding (by controlling) how the bass line and chords move in progression.

Young children and small hands

For young children, small hand size can make chord playing quite uncomfortable. It is fine for them to use two hands to play three notes! The first step is to play two notes, C and E, at the same time, with one or two hands. Notice how they are spaced with a gap of one note. Add another note, with the same gap, above. Voilà! A triad (it's up to you when you give the names of what they are doing). I usually tell them "It is named after the bottom note. Look, you just played a C chord!" Then you can check understanding by holding down a C triad somewhere else on the piano, asking them to look at the notes and say what it is, or getting them to play a C chord higher up or lower down. This kind of game can go on for as long as you wish, and can be repeated in future lessons to keep the foundations secure. Once they are clear about this, you can ask them to find a "G chord" or an "F chord" - or again, play one and ask what it is. Lead them through the process again - which note is the lowest? What gives a chord its name?

Playing chords with left hand

I have found over the years that a high proportion of my students get confused when first asked to play a C chord with the left hand. They will often put their thumb on C and thereby end up with an F chord. Depending on your teaching style, you may want them to learn from this mistake (with potential for a bit of humour) or seek to prevent it by working on building from the bottom up.

Fun with broken chords and arpeggios

Those with big enough hands can have a lot of fun with chords straight away. They can play them up and down the keyboard, as broken chords or hand-over-hand arpeggios, with hands together at different distances, with and without pedal, loudly and quietly... If you can get them to sing the notes as they play it is a great aural training activity (and fun to point out that it's really useful for grade 8!)

Linking to theory

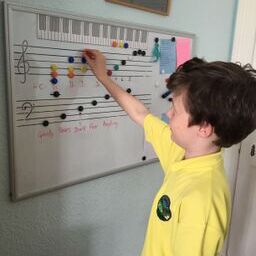

For the theory side of things, link the playing with looking at, and drawing, triads. I have a white board with magnets and staves on it, on which we can place chord notes and move them around. Triads are such a nice cosy stack of thirds that it's easy to recognise them and link that with forming a hand shape to play.

There are many ways to branch out beyond the first basic triad. Normally I will teach the other two "American" left hand chords next so that the student can get on with harmonising easy tunes, such as Mary had a Little Lamb (Merrily we Roll Along). This tune is especially useful as it only needs chords I and V, and it also introduces very naturally the idea that not every note in a tune needs a separate chord. Mary sounds way too frantic if every syllable gets a different chord! However, it is also worth pointing out that with these three chords you can harmonise any note in the scale, albeit not very elegantly.

'American' chords

If you haven't met the "American" chords, they are: I, V7b without the fifth, and IVc. To a student, it's a set of movements: play a C major triad, keep the top note, move the middle note up a semitone and the bottom note down a semitone. You demonstrate this very slowly, and explain how the movement outward by a semitone both ways is like stretching a piece of elastic: it wants to go back to its previous length and that is why a V7 chord is tense, needing to resolve to I. Having resolved to I and checked (and practised) that set of moves, possibly over a week, you start again from I and move to IVc: keep the bottom note this time and move the other two up one white note. Easy!

Building a triad

Later, when putting it in different keys, you will need to go over the movement of the two upper notes by a semitone and a tone respectively and try it in a key such as F where a black note is required. You may also have to explain and practise with them how to build a major triad out of semitones (root plus four semitones gives third, plus three more gives fifth). There is no need to label the chords in the detail given above - that's for teachers who know this notation already. You will nevertheless need some sort of label so you can guide the student into using the chords for accompanying tunes. If you plan to stick with C major for a while, call them "C, G-seventh and F". If not, go for "one, five-seventh and four".

Picking the right chord for the tune

Picking the chord to go with the tune note is another skill that takes a while to embed. You can go back to the theory and use diagrams or notation to show which scale notes feature in which chords; for the aurally or practically minded you can do a trial-and-error session of playing and noticing what goes with what. For the kids who like to know the rules, you can draw up lists of note names per chord: in C major this would be something like "I = C, E, G; IV = C, A, F; V7= D, F, G, B". Maths enthusiasts can draw Venn diagrams of chord notes, overlapping where notes can have more than one chord.

More advanced fun

For more technically advanced students who have grasped how to find C, G and F chords, this is a good time to introduce the 12-bar blues (also mentioned in my article on inventing). Keep the first version they learn very simple indeed, to prevent them stalling at each change of position. I like to teach them to play in root position but many beginner level piece in this style (e.g. "Don't Care Blues" in the Piano Time series) use inversions to keep the hand in one place. A future article will go into more detail about ways to teach this and other standard piano sit-down-and-play favourites such as Happy Birthday.

The Magic Moment!

A magic moment as they develop their chord playing skills is when you introduce them to the "Four Chords" of the ubiquitous 4-chord songs of current pop music. This really feels like being let in on a trade secret. Depending on how well they find chords and how they remember which is which, you can lead them through using theory or a more visual/ kinaesthetic approach. In both cases, it is best to link them (when the moment is right for the student's understanding) to their Roman numerals, so that you can move on to finding chords by ear from songs on YouTube. The theory-based explanation is essentially finding C, F, G and then A minor triads and counting the position of each root in the scale. The other approach is to use the well-worn "Heart and Soul" progression of I-vi-IV-V and explain it in terms of how it looks and how the hand moves:

"Play a C chord. Look at the lower two notes. See how they are evenly spaced. Hang on to those two, and add one the same distance below....Listen to that chord. Look at the root/lowest note. What is it?" (I prefer to get them calling it "A minor" rather than just "A" even if they don't understand entirely why).

"OK, now do the same thing again (keep two and add one below). What have you got now?" (It's up to you whether you do some consolidating at this point or go straight on to the final chord)

"Now take that whole F chord and move everything up one note, to a....G chord - remember those? Those are your four chords, now can you find your C chord? and start the whole process again!"

The duet that everyone knows

This will often trigger recognition of the Heart and Soul duet which so many children pick up from each other anyway. In that case you can launch straight into playing it with your student (I use these occasions as a chance for some sneaky improvisation practice of my own). If not, you can teach them it!

Games

If you introduce them to the extra task of saying "one...six...four...five" as they play, and give them enough time to absorb the connections, a next step can be a game of calling out (one of these four) chord numbers in any order to see how quickly they can find them. You can also get them to call out the numbers, play the chords yourself and ask whether your chord sounded right (keep them mostly correct, at first, so the aural link is secured).

More songs

There are so many 4-chord songs out there that it is really for you to trawl the tracks and pick songs that you think they will relate to. I have recently been using "Counting Stars" (One Republic) as a starting point, as it consistently repeats vi-I-V-IV throughout and most of my students have heard it. Adele's "Hello" is another one which uses these four at first, but beware, it then uses different progressions, including use of chord iii, a three-chord link and a varying order of the usual four in the chorus. With your more aurally aware students you can go over this and point out the differences.

I make a note, and keep it readily to hand, of the progressions in different pop songs, as and when they crop up in exploring YouTube with students. This saves time later and helps reinforce the joyful news that an awful lot of them are the same!

Singing too!

Incidentally, this skill of finding and playing the chords is instantly usable if the student just sings the melody, rather than trying to play it. It is often too technically demanding to find the notes of the tune at the same time - and very frequently the vocalist may use indeterminate pitches or the words may cause a lot of rhythmically complex repetition, any of which just gets in the way of fluency on the piano, not to mention not sounding very convincing. And how cool is it anyway to be able to sit down at a keyboard with your pals and accompany a singalong with basic triads?!

There will be more about this when we look at Ear Playing and Geography... After all, Adele doesn't sing "Hello" in C major, does she?

Janet Noakes